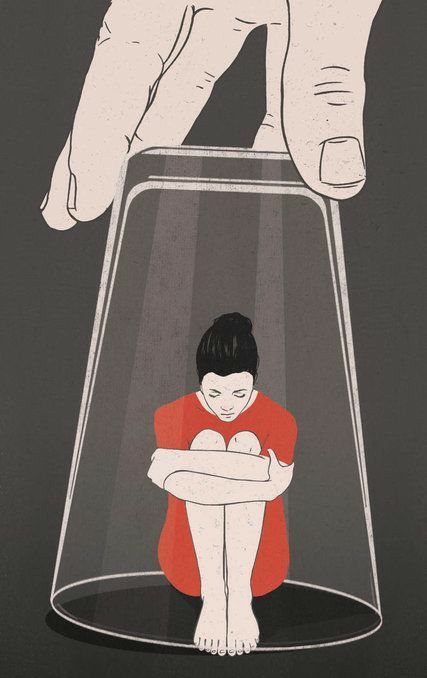

Deviance is not an intrinsic quality of an act, but the result of social definition processes. A person becomes “deviant” when audiences with power (institutions, authorities, media, peers) successfully apply a label. That label reshapes identity, opportunities, and relationships, and can increase the likelihood of future deviant behavior.

Key authors and contributions

Frank Tannenbaum (1938) – Dramatization of evil: the public reaction fixes a deviant identity that is more damaging than the original act.

Edwin Lemert (1951) – distinguishes:

-Primary deviance: occasional acts with no impact on self-identity.

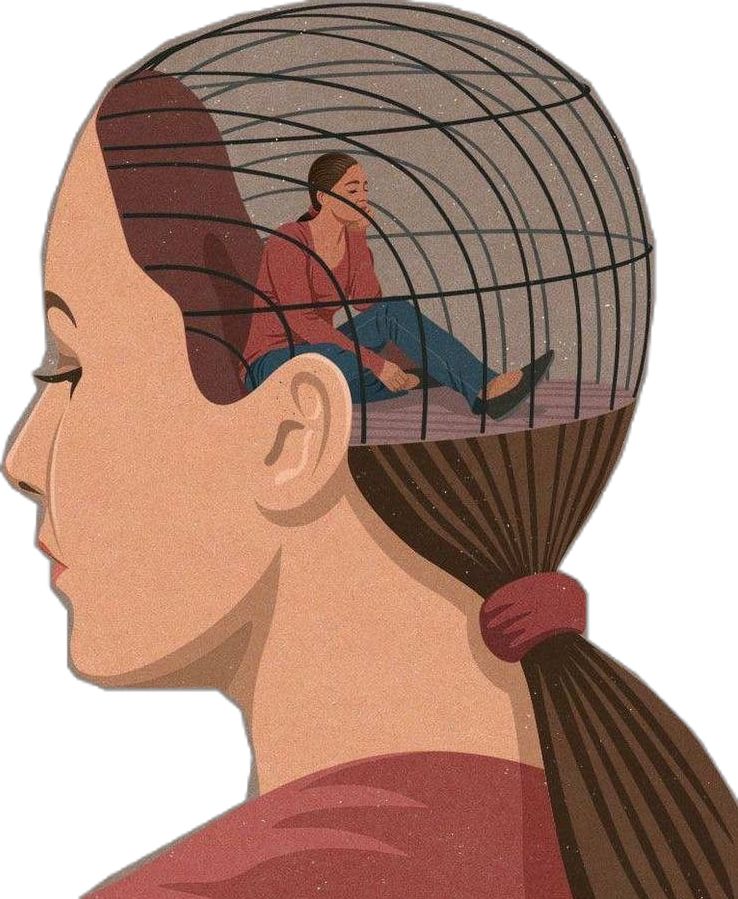

-Secondary deviance: emerges when the label is internalized and the person reorganizes their life around that role.

Howard S. Becker (1963) – Outsiders:

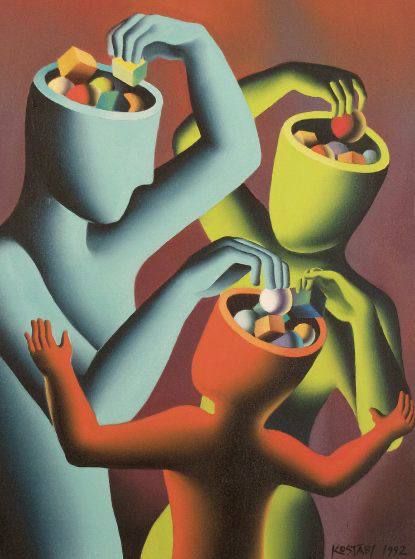

-“Moral entrepreneurs” create and enforce rules.

-Deviant = “someone who has been successfully labeled as such.”

-Idea of a deviant career and focus on social control.

Erving Goffman (1963) – Stigma: stigma degrades social status and shapes interaction, managed through concealment, “passing,” or strategic disclosure.

Frank Tannenbaum

Typical process (mechanism)

–Act/attribute (often ambiguous or minor).

–Selective detection (biases by class, race, gender, neighborhood, visibility).

–Public definition (media, rumors, authorities) + rule enforcement.

–Imposition of a label (formal: record, diagnosis; informal: reputation).

–Collateral consequences: loss of opportunities, surveillance, exclusion.

–Identity reorganization: internalization of status, search for like-minded subcultures → secondary deviance and career.

Important concepts and distinctions

–Primary vs. secondary deviance (Lemert).

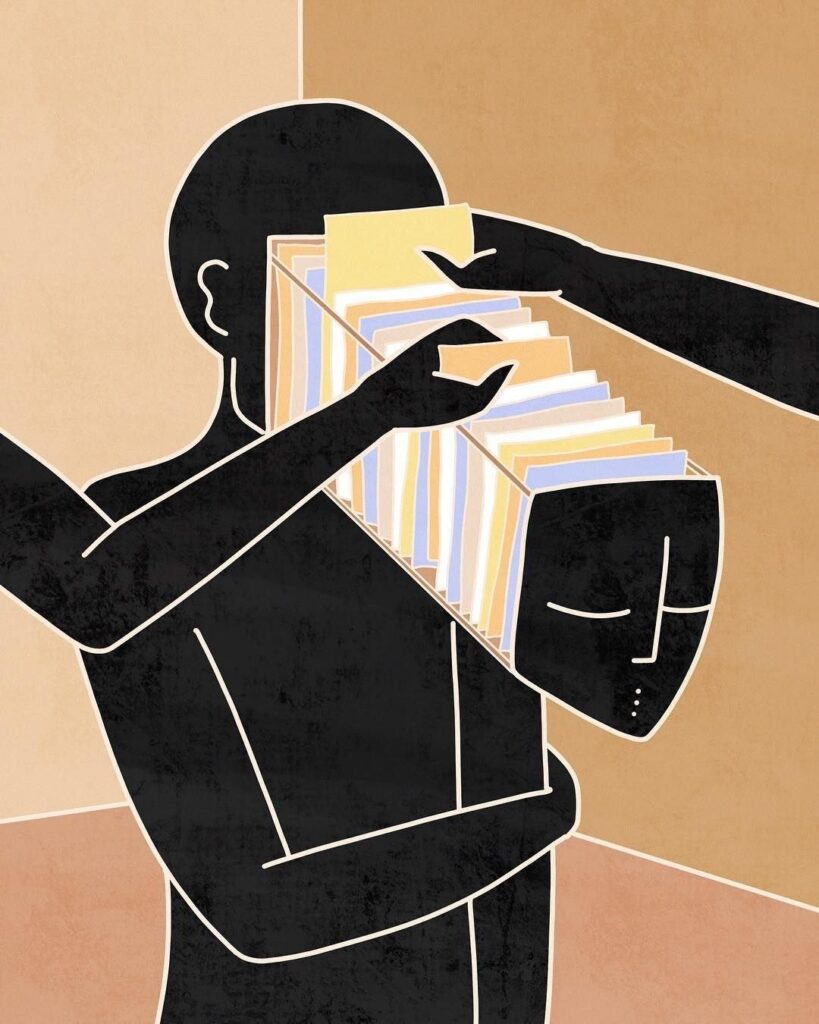

–Stigma (Goffman) and discredited vs. discreditable identity.

–Moral entrepreneurs (Becker) and moral campaigns/moral panics.

–Deviant career: trajectory of roles, networks, and commitments tied to the label.

–Selectivity of control: not everyone who acts the same is labeled the same.

Strengths

Focuses on how social control produces and sustains deviance.

Explains differences in treatment of similar behaviors (bias/selection).

Connects micro-interaction to life trajectories (careers).

Critiques

Origin of the first act: better explains persistence than the onset of deviance.

Relativism: risk of downplaying real harm if everything is reduced to social reaction.

Agency and structure: may undervalue individual motivations and structural conditions (poverty, inequality).

Variation: not all labels are internalized; there is resistance and de-labelling.

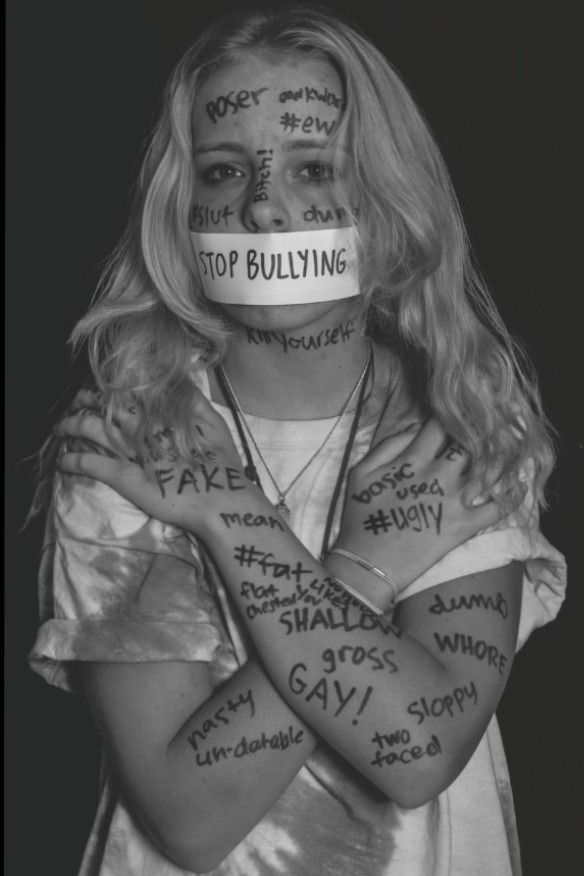

WHY IS LABELING PEOPLE HARMFUL?

Labeling people is harmful because it activates a chain of psychological, social, and institutional effects that reinforce each other:

What happens at the personal level

–Self-fulfilling prophecy: if you’re treated as “problematic,” “lazy,” or “dangerous,” you’re more likely to act in line with that expectation.

–Reduced identity: a label simplifies who you are (“the troublemaker,” “the weird one”) and eclipses your other traits and achievements.

–Stigma and shame: the label degrades social status, affects self-esteem, and can isolate you.

–Stereotype threat: reminding someone of their stigmatized “category” worsens performance (exams, interviews, etc.).

What happens in relationships and the community

–Confirmation bias: after labeling, people look for evidence that confirms the label and ignore the contrary.

–Less support, more surveillance: those with a “bad reputation” receive less help and more sanctions, even when doing the same as others.

–Spiral of distrust: the labeled person distrusts the institution; the institution responds with more control; conflict grows.

What happens in institutions (snowball effect)

–Closing of opportunities: records, rumors, or diagnoses turned into “status” block access to jobs, housing, education.

–Deviant trajectories: the label opens doors to groups and contexts where that identity is consolidated (what the theory calls a “career”).

–Structural inequity: labels are applied selectively (by neighborhood, class, ethnicity, gender), amplifying inequalities.

Quick examples

–School: a student labeled “disruptive” is monitored more, sanctioned sooner, and receives lower academic expectations → performs worse.

–Work: “not trustworthy” translates into fewer high-visibility projects → fewer merits → the label “confirms” itself.

–Justice: a minor record becomes a lifelong barrier.

–Mental health: a diagnosis is used as a total identity (“he’s bipolar”), provoking infantilizing treatment and social exclusion.

How to avoid harm (what to do instead of labeling)

–Describe behaviors, not identities: “you were late three times” instead of “you’re irresponsible.”

–Focus on situational and modifiable factors: concrete causes, trainable skills, and improvement plans.

–Person-first language: “person with…,” not “the ….”

–Private, specific feedback; separate behavior from personal worth.

–Bias review: data and metrics before making decisions that “stick” reputations.

–Second chances: sealing records, restorative justice, periodic evaluations that allow “de-labeling.”

WHAT IF THE LABEL IS POSITIVE INSTEAD OF NEGATIVE?

Positive labels also have powerful effects. They can help… and harm.

–Pygmalion effect: high expectations → more support and opportunities → better performance.

–Stereotype lift/boost: feeling valued can increase motivation and confidence.

–Signaling: opens doors (“talented,” “leader”) that wouldn’t otherwise open.

The risks (when it becomes “identity”)

–Pressure and anxiety: “I have to live up to it” → fear of failure, perfectionism, avoidance of challenges.

–Fixed mindset (praise the person, not the process): “I’m smart” → avoid difficult tasks to not “lose” the label.

–Moral licensing / blindness: “he’s a good kid” → failures are minimized; unfair behavior is tolerated.

–Boxing-in: “you’re the creative one / she’s the responsible one” → roles and learning are restricted.

–Resentment and inequality: perceived favoritism; others receive less feedback and fewer opportunities.

–Fragile identity: if performance drops, impostor syndrome or a sharp fall in self-esteem appears.

–Tokenism and essentialism: turning someone into “the face” of a group or a “natural talent” invisibilizes effort and complicates relationships.

How to use “positive labels” without harm

–Praise the process, not the essence: “you spent three afternoons iterating and asked for feedback” > “you’re a genius.”

–Be specific and bounded: describe behaviors/impacts (“your report clarified X and enabled decision Y”), not global identities.

–Make them reversible: the “label” should be a state that is earned and learned, not a fixed trait.

–Balance opportunities: rotate high-visibility projects; use clear criteria to avoid favoritism.

–Normalize error: errors = information; celebrate learning from failure, not hiding it.

–Check biases: review data before giving awards/promotions; cross-check with peers; use blind evaluations when possible.

–Invite stepping out of the role: offer challenges outside their “strength” to broaden repertoire and avoid pigeonholing.

Positive labels motivate in the short term, but if they become a fixed identity they can generate pressure, bias, and inequality. Use them as temporary, behavior-based descriptions oriented toward learning.

CAN THIS LEAD US TO THINK THAT ANY THOUGHT OR TERM CAN BE HARMFUL IF TAKEN TO THE EXTREME?

I’d say yes, with nuance: almost any idea or term, if absolutized and made rigid, can end up doing harm. Not because of the word itself, but how we use it. Think of this as an “inverted U” curve: a little label/belief orders and orients; taking it to the extreme impoverishes, distorts, and excludes.

Why extremes harm?

–Loss of nuance: it becomes all-or-nothing (“always/never,” “good/bad”), and reality is rarely binary.

–Essentialism: we move from describing behaviors to defining identities (“you are X”), which stick and are hard to undo.

–Self-fulfilling prophecies: very strong expectations shape behaviors and perceptions until they “confirm” themselves.

–Confirmatory blindness: we only see what fits the label/belief and ignore the rest.

–Moral licensing: a “good” label can justify abuses.

–Anxiety and pressure: positive labels taken to the extreme generate fear of failure and a fixed mindset.

When does a label or thought start to be harmful?

–Rigidity: doesn’t admit exceptions or revision (“no matter what, it’ll stay this way”).

–Power and consequences: it’s used by someone/institution capable of closing doors (school, company, justice system).

–Irreversibility: remains in records, reputations, or diagnoses with no clear paths to “de-label.”

–Saturation: repeated so much that it eclipses everything else about the person/situation.

–Identity fusion: the person sees themselves only through that lens (self-imposed or imposed by others).

–Lack of diverse feedback: no data or voices that question it.

How to keep the useful without going to extremes

–Describe behaviors, not essences (“you did X, it impacted Y”) and use time horizons (“this week…”).

–Treat the label as a hypothesis: falsifiable, provisional, and contextual.

–Review periodically: does it still fit? are there counterexamples?

–Multiply lenses: combine several descriptions instead of a single identity.

–Keep balance: acknowledge strengths and areas for improvement in the same conversation.

–Create exits: define clear conditions to change or remove the label.

THE ESSENTIALISM

It’s the tendency to believe that categories like “the shy,” “the criminals,” “the geniuses,” “the X (group)” have an internal, fixed, hidden essence that:

–Causes how they are and behave.

-Is immutable (doesn’t change over time).

-Makes members homogeneous among themselves (and very different from others).

-Draws sharp boundaries (“either you are or you aren’t”).

In psychology we talk about psychological essentialism (how we reason about categories) and, socially, social essentialism (applied to identities: gender, ethnicity, class, professions, diagnoses, “talents,” etc.).

Signs we’re essentializing

–Reifying labels: “he’s a loser / a born leader / a toxic person.”

–Always–never: “he’ll always do X,” “she’ll never change.”

–Mystical or biological causality: “it’s in his blood,” “it’s his nature.”

–Erasing context: ignores circumstances, incentives, learning, power.

–All-or-nothing: discrete categories, no gradations (“intelligent vs. not”).

The essentialism is problematic?

–Closes off change: if “that’s how they are by essence,” why teach, rehabilitate, or give second chances?

–Reduces the person to a single label (pigeonholing).

–Amplifies prejudice: overgeneralizes traits to an entire group.

–Biases decisions: hiring, sanctions, diagnoses become rigid.

–Dehumanizes: by attributing a fixed “nature” to groups, it facilitates unfair treatment.

–Self-essentialism: believing “I am (or am not) X by essence” fuels perfectionism, fear of error, or learned helplessness.

How it connects to labelling theory

A label becomes dangerous when it’s essentialized: it shifts from describing a behavior (“he was late”) to defining a stable identity (“he’s irresponsible”). That leap makes social reaction harsher and self-fulfilling (less support, more surveillance → more failures).

Quick examples

–School: “she’s bad at math” → avoids challenging courses → less practice → confirms the label.

–Work: “he’s the ‘creative one,’ she’s the ‘organized one’” → biased assignments that limit development.

–Justice: “criminal by nature” → longer sentences, fewer reintegration programs.

–Mental health: diagnosis treated as a total identity (“he’s a…”) instead of a treatable condition.

Non-essentialist alternatives (practical)

–Process language: “not yet,” “is learning,” “this week showed…”.

–Person-first: “person with… / who did…,” not “is a…”.

–Describe observable behaviors with time and context: what happened, when, where, with what effects.

–Dimensions > categories: think in continua (anxiety, impulsivity, skill) with degrees, not boxes.

–Incremental theory (growth mindset): abilities as trainable.

–Data > impressions: review evidence of within-group variability and change over time.

–Role rotation and cross-opportunities to avoid pigeonholing.

–“De-labelling” rituals: explicit criteria to update or remove labels (e.g., after N weeks of consistent behaviors).

What an “anti-essentialist” system would look like

- Psychological layer (individual)

Training in probabilistic thinking: base rates, uncertainty, “not yet,” alternative causes.

–Process and context language: describe behaviors with time/place rather than traits (“today he interrupted 3 times in the meeting”).

–Review habits: look for counterexamples, write hypotheses and a review date.

–Cross-exposure: rotate roles and groups to see within-group variability (a natural antidote to “they’re all X”).

- Relational layer (teams, classrooms)

–Feedback norms: specific, behavioral, with an improvement plan and “de-labelling” criteria.

–Rotating roles and changing partners: prevents pigeonholing (“she always coordinates,” “he always analyzes”).

–Update rituals: brief meetings to review perceptions (“what did we see this week that contradicts our labels?”).

- Institutional layer (rules and processes)

–Evidence-based evaluations: rubrics with observable indicators + time windows; forbid identity descriptors in records.

–Blind review where appropriate: selection/promotions with partial anonymization to cut prior labels.

–Status sealing/expiration: records, diagnoses, or ratings with an expiration date unless renewed evidence appears.

–Bias metrics and audits: inspect who receives which labels, with what effects, and correct asymmetries.

–Second-chance policies: formal reintegration pathways (equivalents to “ban the box,” restorative justice, etc.).

- Cultural layer (symbols, media, education)

–Change narratives: celebrate trajectories (before–during–after) more than “innate talents.”

–Person-first language in manuals and internal media.

–Anti-essentialist curriculum: development, plasticity, history of categories (show that they change and why).

- Technological layer (systems design)

–Interfaces that force context: required fields for “observable evidence” and “time horizon” before saving an evaluation.

–Absolutism alerts: detect “always/never,” “is X” and prompt behavioral reformulation.

–Recommenders with explanations: reasons and limits of each prediction (probabilities, confidence bands).

Limits and trade-offs

–Cognitive cost: thinking in dimensions/context takes more effort than using fixed labels.

–Need for coordination: law, health, and safety require categories; we’ll have to keep them, but with reviews and appeals.

–Risk of paralysis: too much doubt slows decisions; that’s why we use thresholds and review dates, not total certainty.

–Identity and belonging: people seek positive labels; the solution is to make them soft, earnable, and revocable, not abolish all identity.

How to measure if it works

–Reduced persistence of labels (more documented changes/updates).

-Smaller gaps in opportunities and sanctions between comparable groups.

–More role mobility and diversity of performance over time.

–Better outcomes (performance, climate, recidivism, satisfaction) without increasing critical errors.

Conclusion

A world without essentialism isn’t viable; a world with constrained, reversible, low-harm essentialism is. It’s achieved by combining language, habits, rules, technology, and culture that force us to describe behaviors, set contexts, and review judgments. That architecture doesn’t eliminate our intuitions, but changes the incentives so the essentialist shortcut no longer dictates important decisions.

In my opinion, essentialism can be important in society if it is controlled and not used to exclude people. I believe that a society without exclusion would be possible if we all had more ability to empathize with others’ stories and beliefs, just as there would also be a decline in mental illnesses such as anxiety or burnout syndrome by not having the social pressure to be ‘perfect.’ It would open many paths for multi-education, and people would have more tools to perform well at work.

What do you think about labeling theory and essentialism? Do you think it’s important, or on the contrary, do you think it should be eradicated from society?

Leave a Reply