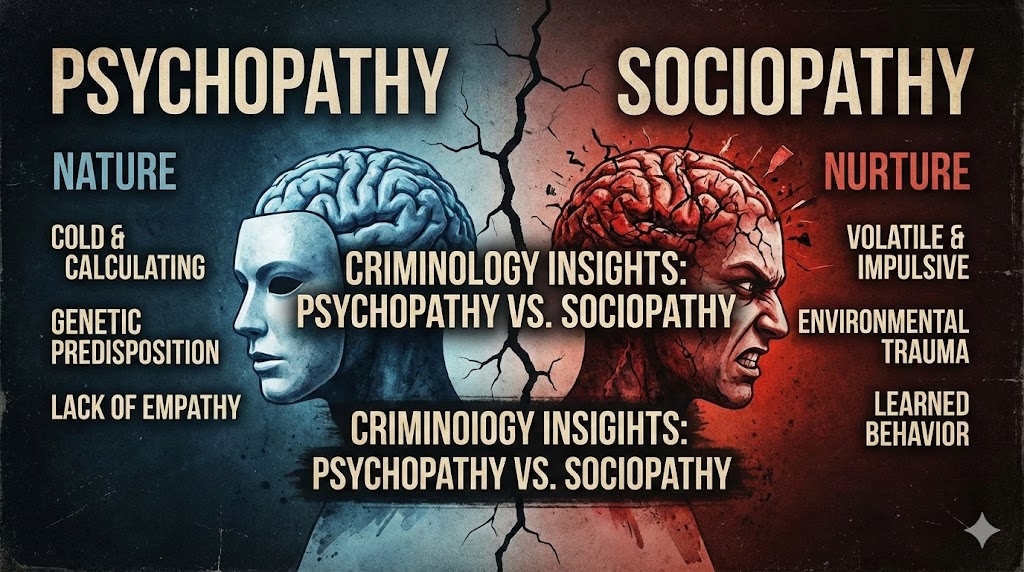

The study of crime has been marked by multiple theoretical currents seeking to answer one of criminology’s most persistent questions: why do people commit crimes? For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, biological and psychological explanations predominated, attributing crime to innate traits, mental deficiencies, or individual predispositions. However, these theories were insufficient to understand the complexity of the criminal phenomenon, as they ignored the influence of the social and cultural environment in which individuals develop.

In this context, the American criminologist Edwin H. Sutherland formulated his famous Differential Association Theory in 1939, published in Principles of Criminology. This theory represented a fundamental shift in criminological thought, proposing that crime is not a biological or psychological product, but a behavior learned through interaction with other people. In other words, delinquency is transmitted in the same way as any other social behavior.

Sutherland’s proposal is based on the idea that individuals learn both the techniques for committing crimes and the justifications and values that legitimize these behaviors within primary socialization groups (family, friends, gangs, organizations). Thus, frequent, lasting, and intense contact with definitions favorable to law violation increases the likelihood that a person will adopt criminal behaviors. The theory highlights that criminality does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it is incubated in social contexts where delinquent behavior is normalized and reinforced. Its deepest detail focuses on the learning process and its scope in explaining all types of criminality.

Key Principles of Criminal Learning

- Criminal behavior is learned, not inherited or spontaneously generated.

- It is learned through interaction with other people, via verbal or gestural communication.

- The learning of criminal behavior occurs primarily in intimate, personal groups (family, friends, gangs), not through impersonal means like movies or the press.

- The theory states that delinquent behavior is not simply the imitation of an act, but a learning process that encompasses multiple elements:

- Techniques of Commission: The individual learns the methods for carrying out the crime. In common crimes, these may be simple techniques (like picking a lock); in White-Collar Crime, they can be complex techniques (like creative accounting or tax evasion).

- Motivations and Justifications (Rationalizations): This is the core of the learning process. The individual internalizes a set of “definitions” or interpretations. These definitions can be:

- Favorable to law violation: They justify the crime (e.g., “Everyone does it,” “The government steals the money, why should I pay taxes?”).

- Unfavorable to law violation: They reinforce respect for the law.

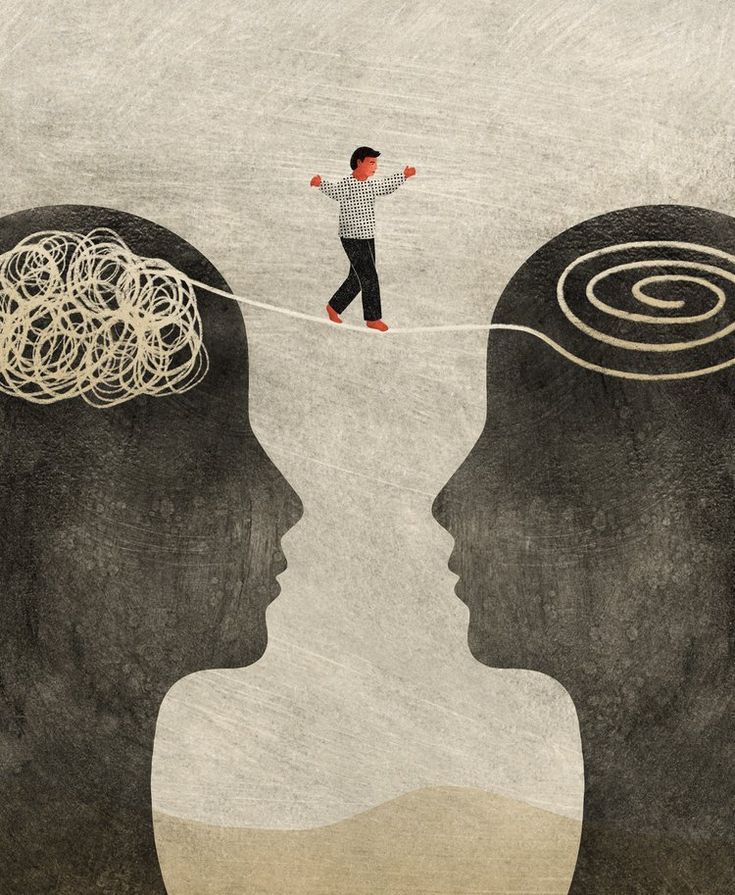

- Differential Association Principle: An individual becomes delinquent when the balance of these definitions (those favorable to law violation) outweighs the contrary definitions. It is a scale where pro-crime messages win over anti-crime ones.

- The orientation of motives and impulses is a function of the favorable or unfavorable interpretation of legal provisions.

- A person becomes delinquent when, in their environment, definitions favorable to law violation outnumber the unfavorable ones.

- Differential association varies in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity:

- Frequency: How often the interaction occurs.

- Duration: How long the interaction lasts.

- Priority: When in life it occurs (e.g., in childhood carries more weight).

- Intensity: How important the person/group being learned from is.

- The process of learning crime is similar to that of any other behavior.

- Although needs and values can influence behavior, they do not, by themselves, explain crime, because people with the same needs don’t always offend (e.g., poverty ≠ automatic delinquency).

Core Concepts

- Not all poor people commit crimes, nor are all rich people innocent: the decisive factor is the social and relational environment.

- Primary groups (family, friends, peers) are more influential than secondary ones.

- The theory is highly effective in explaining organized crime.

- Differential Association: refers to the fact that the probability of an individual becoming delinquent increases when their associations (contacts) with criminal patterns or models exceed their associations with anti-criminal models.

- Learning: Crime is a behavior acquired through social interaction, including not only the techniques, but also the justifications and the attitude toward the law.

- White-Collar Crime: Sutherland pioneered the study of this type of criminality (committed by people of high socioeconomic status during the course of their occupation). Differential association theory was crucial in explaining that these crimes are also learned within corporate or business groups, with their own justifications and techniques.

Applications

- Juvenile Gangs: Young people learn criminal techniques and justifications within the group.

- Corporate Crime: In companies where corruption is normalized, employees learn that “cheating” is part of the job.

- Prisons: An inmate can leave with more criminal knowledge because they learn from other inmates.

Criticisms

Despite its influence, the theory has received several criticisms:

- Difficulty in Measurement: It’s almost impossible to quantify the key variable: the “excess” of definitions favorable to law violation over the unfavorable ones. The exact tipping point of the scale cannot be objectively measured.

- The “First Offender”: The theory does not satisfactorily explain how the first individual who commits a crime emerges, or how a new criminal behavior originates—i.e., who taught the person who started the chain?

- Individual Passivity: Some critics point out that the theory presents the individual as an overly passive subject who merely absorbs their environment, failing to sufficiently consider rational choice or personality characteristics that might influence which associations they seek or adhere to.

Practical Example

Imagine an adolescent in a neighborhood with a high gang presence:

- Their friends teach them how to steal motorcycles (technique).

- They are told that “everyone steals because the system is unfair” (justification).

- Since they spend a lot of time with them and they are their reference group (intensity and duration), the teenager internalizes these behaviors as normal.

- In the end, the scale of “definitions favorable to crime” outweighs the unfavorable ones → they become delinquent.

Importance in Criminology

- Decoupled criminality from the lower classes: It explained that crime is not exclusive to the poor or people with pathologies, but is a learned behavior that can occur in any social stratum, including the elite (white-collar crime).

- Emphasized the social and cultural environment: It highlighted the influence of the social circle and culture in the development of criminal behavior.

- Laid the foundation for learning theories: It paved the way for later theories that also focus on how deviant behavior is acquired.

White-Collar Crime

One of Sutherland’s great contributions was creating a general theory that could explain criminality across all social classes.

- Application to the Elite: He demonstrated that executives or high-status professionals commit crimes (fraud, corruption, stock manipulation) that are learned in the corporate environment. In this context, differential associations occur in the office, the boardroom, or the business network, where “techniques” and “rationalizations” for violating the law without losing social prestige are taught.

- Cultural Conflict: Sutherland’s original theory connects to cultural conflict in society. Social disorganization generates multiple groups with different norms. Criminal behavior is, therefore, the expression of a differential social organization (subcultures) that is in conflict with the norms of the dominant culture.

Leave a Reply