Why Some Crimes Are Culturally Accepted

Law and morality do not always coincide. Some acts are criminalized in the penal code but, in social practice, receive tolerance, justification, or even moral approval in certain contexts. Understanding why this happens requires a simultaneous look at history, power structures, cultural norms, psychological mechanisms, and the way rules are enforced. This article deconstructs that phenomenon: what explains it, what theories help us understand it, prototypical examples, and what it implies for public policy and social coexistence.

Law vs. Morality? — A Useful (and Problematic) Distinction

The law is a set of rules formalized by a state authority and sanctioned by the repressive apparatus (fines, imprisonment, prosecution). Morality consists of social norms and values—often informal—that regulate what a community considers right or wrong. Although both regulate conduct, they stem from different origins: the law relies on formal procedures and legitimacy; morality on culture, tradition, and public opinion.

This separation means there can be:

- Legal actions considered immoral by large sectors (e.g., aggressive business practices that are not illegal but elicit rejection).

- Illegal actions morally accepted by the community (petty theft out of necessity, civil disobedience, some traditional land uses, etc.).

The friction between these two planes is fertile ground for social tolerance: when the law fails to connect with moral intuitions or real needs, society displaces its mandatory nature.

Mechanisms Explaining the Social Acceptance of Certain Crimes

Below are the processes that most commonly allow an illegal act to be socially tolerated or legitimized:

- Perception of Injustice or Illegitimacy of the Law If the law is viewed as unjust, arbitrary, or imposed by interests outside the community, compliance weakens. When a norm does not reflect shared values, people seek moral shortcuts: disobeying it can be seen as legitimate.

- Economic Need and Survival In contexts of poverty or lack of a welfare state, behaviors such as informal trade, scrambling to make ends meet (or hustling/making a living), or appropriation of resources can be perceived as legitimate responses to need, not as “moral crimes.” The community’s morality prioritizes survival.

- Normalization Through Repetition and Practice When a certain illegal behavior is repeated without effective sanction, it shifts from being exceptional to commonplace. Repetition normalizes it and reduces the perception of severity (“everyone does it”).

- Neutralization and Justification Neutralization techniques described by Sykes and Matza (e.g., “I had no choice,” “the victim deserves it,” “everyone does it”) allow individuals to rationalize illegal conduct and society to accept it.

- Cultural Differences and Legal Pluralism In societies with a plurality of norms (customs, religious laws, and state institutions coexisting), what is a crime for the State may be accepted by local or religious norms. This is the realm of plural legality.

- Time Lag: Lagging Laws Rules change slower than social values. Acts that were once punished may become morally obsolete (and eventually be decriminalized), while other behaviors are criminalized before gaining moral consensus.

- Power, Status, and Selective Enforcement Crimes committed by elites are often perceived with less social disapproval, especially if the perpetrators control the discourse and sanctions. Impunity or differentiated treatment contributes to cultural acceptance.

- Political Disobedience and Moral Legitimacy Illegal actions aimed at changing an injustice (civil disobedience, symbolic sabotage) can enjoy strong moral support if the perceived goal is just.

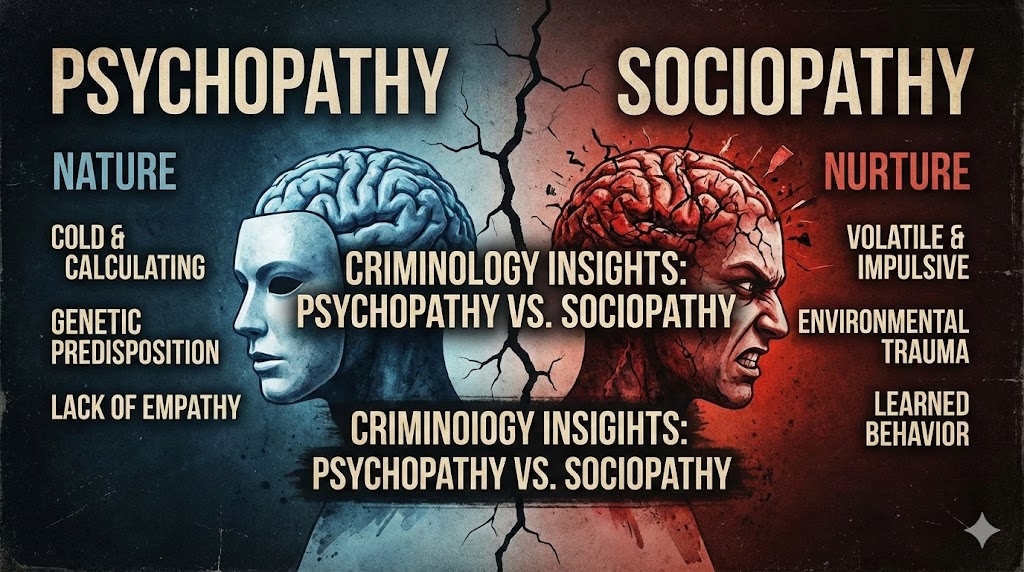

Theoretical Frameworks That Help Understand It

Several approaches from sociology and criminology shed light:

- Labeling Theory (Becker): Crime is not just what is done, but what society labels as such. The label transforms the actor’s identity and public perception.

- Anomie / Strain Theory (Merton): When cultural goals are unattainable through legitimate means, deviant means appear that the community may tolerate.

- Social Learning / Differential Association (Sutherland, Bandura): Behaviors are learned through interaction; a subculture that normalizes a practice transmits it.

- Neutralization (Sykes & Matza): Justifications that reduce moral blame.

- Social Control (Hirschi): The strength of social bonds (family, school, community) determines adherence to the law; their weakening facilitates tolerance for deviance.

- Legal Pluralism and Legal Anthropology: State norms compete with local and religious norms.

Concrete Examples (Types and Common Cases)

To better understand, here are some examples—prototypical but with nuances—of crimes that are often culturally tolerated in different contexts:

- Petty Theft Out of Necessity: When basic necessities are inaccessible, minimal theft may receive sympathy and not generate severe stigma.

- Informal Economy: Street vending, occupation of public spaces, undeclared services; these are illegal or regulated, but socially accepted because they sustain livelihoods.

- “Soft” Corruption or Clientelism: Practices of exchanging favors and petty corruption (or small-scale corruption) tolerated as part of local social functioning.

- Civil Disobedience: Illegal protests and blockades that public opinion approves of as legitimate means of pressure.

- “Civil” Transgressions: Running red lights, speeding on certain streets, or minor administrative fraud often fall into the category of “social lapses” or “minor offenses.”

- Traditional Practices Contrary to the Law: Collective uses of land, traditional marriages prohibited by legislation, rituals that may conflict with state norms.

(Important: Acceptance is relative: what one community tolerates may be condemned by another; internal tensions always exist.)

What Are the Consequences of This Tolerance?

- Distortion of Justice: Unequal application erodes confidence in institutions.

- Legitimization of Structural Illegality: When large sectors deem the law illegitimate, the social contract is lost.

- Normative Adaptation: In some cases, social pressure leads to legal reforms (decriminalization, regulation).

- Selective Stigmatization: Certain groups (youth, the poor, minorities) bear the burden of stigma while others evade consequences.

What Can Public Policy and Civil Society Do?

If the goal is to reduce harm and restore legitimacy, some practical strategies are:

- Participatory Diagnosis: Identify why the norm is rejected or ignored (poverty, ineffectiveness, injustice).

- Align Laws and Values: Open democratic processes that allow for the updating of norms disconnected from social reality.

- Restorative Approaches: Prioritize repair and reintegration over punitive punishments for minor crimes caused by necessity.

- Equitable and Transparent Enforcement: End selectivity and impunity for elites.

- Civic and Moral Education: Promote public deliberation on norms and values.

- Regulation Instead of Prohibition: When prohibition fails, regulation (e.g., sex work, consumption of certain substances) can reduce harm and legitimize controls.

Conclusion

The fact that an act is illegal does not guarantee the community will consider it immoral. The social acceptance of certain crimes is a mirror reflecting inequalities, institutional failures, customs, and psychological justification processes. Understanding this phenomenon requires combining theory and concrete cases, and thinking not only about punishment but also about how to update norms, repair damages, and strengthen legitimacy. Ultimately, the tension between morality and law is an opportunity: it forces us to democratically decide which behaviors deserve reproach, which deserve repair, and which require normative redesign.

Leave a Reply