The Clever Hans Effect (or Handler/Experimenter Bias Effect) is a psychological phenomenon illustrating how the involuntary expectations and cues of an experimenter, handler, or audience can subtly influence the behavior of a subject (animal or human), causing them to produce the expected result without actually possessing the attributed skill.

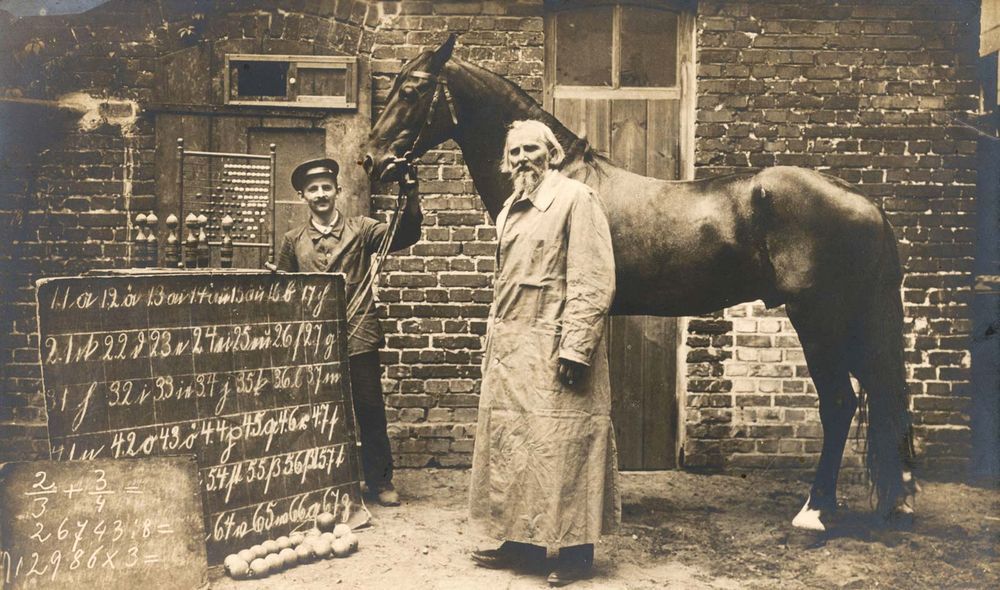

The name comes from the famous German horse named Clever Hans (“Hans the Smart” or “Hans the Wise”) in the early 20th century.

The Case of Clever Hans

Clever Hans was a horse owned by Wilhelm von Osten, a German math teacher, who claimed to have taught him to add, subtract, multiply, divide, solve fraction problems, tell time, spell, and answer complex questions. Hans seemed to respond by stomping his hoof the correct number of times.

In light of the admiration and skepticism, the German Board of Education formed the Hans Commission in 1904. This commission, made up of a veterinarian, a circus manager, cavalry officers, and teachers, found no evidence of intentional fraud by von Osten.

German psychologist and comparative biologist Oskar Pfungst conducted a more rigorous investigation. Through meticulous experiments, he discovered that:

Hans only succeeded when the person asking the question knew the correct answer. Hans only succeeded if he could see the interrogator. If he was blindfolded or the person positioned themselves so he couldn’t see them, the success rate dropped drastically.

Hans was not performing mathematical calculations. The horse had learned to be extremely sensitive to subtle changes in human body language and posture. When Hans started stomping his hoof, the person who knew the answer (von Osten or a member of the audience) involuntarily showed slight tension or leaned forward. Upon reaching the correct number of stomps, that person unconsciously gave a cue of relaxation or a slight movement of the head or body that signaled Hans to stop.

Definition and Mechanism of the Clever Hans Effect

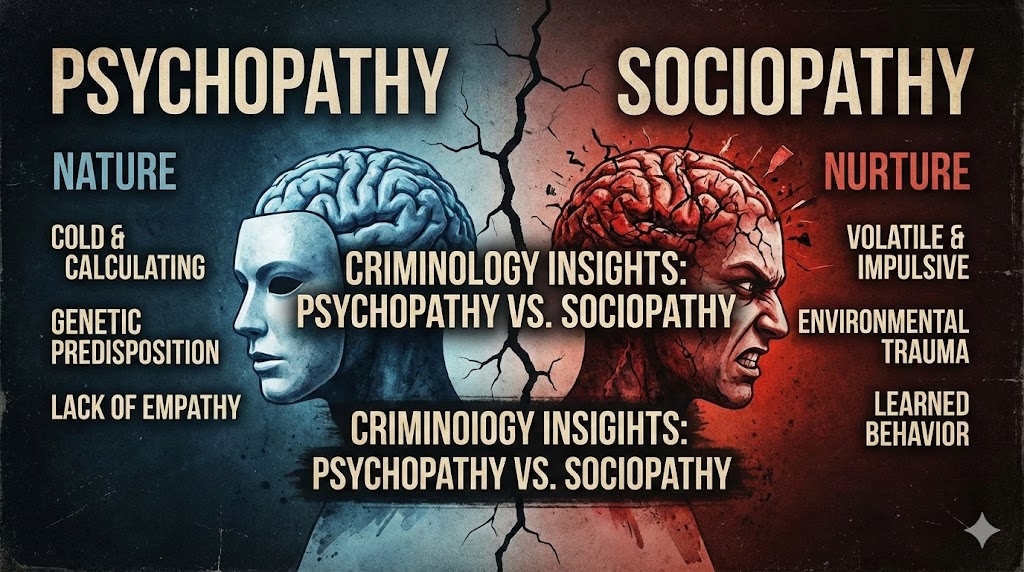

The Clever Hans Effect is an example of observer-expectancy bias.

Definition: It is the unintentional influence of the experimenter, handler, or interrogator on the subject’s behavior, because the experimenter holds an expectation about the outcome.

Mechanism: The experimenter, expecting a particular result, emits subtle, unconscious, non-verbal cues (changes in voice tone, body posture, facial micro-expressions, slight movements, etc.). The subject (in Hans’s case, the horse) learns to interpret these cues as the key to providing the “correct answer” or the expected behavior, without truly understanding the task.

Lack of Intent: It is crucial to understand that, in most cases, the person giving the cues is not aware they’re doing so, and the animal or subject is not “cheating” intentionally, but rather responding to subtle conditioning.

Importance and Application in Science

The discovery of the Clever Hans Effect had a monumental impact on the methodology of scientific research, especially in comparative psychology, animal cognition, and human research.

Experimental Methodology: It demonstrated the critical need to design experiments that neutralize experimenter bias.

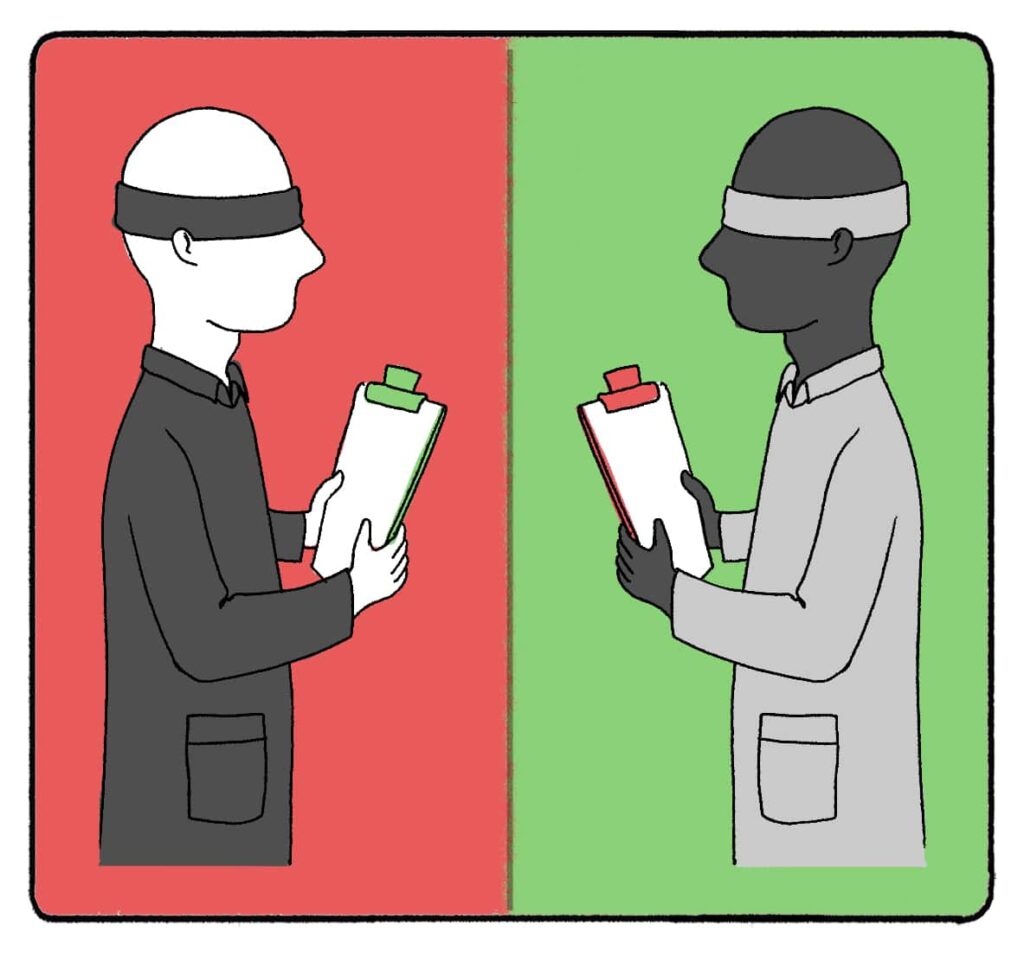

Double-Blind Experiments: The main methodological development to avoid this bias is the double-blind technique. In a double-blind experiment:

The subject (participant or animal) does not know which experimental group they belong to. The experimenter/handler also does not know which group the subject belongs to or what the correct expected result is for each test or individual. This prevents the experimenter from unconsciously transmitting an expectation.

Animal Cognition: It is a fundamental consideration in the study of animal intelligence, animal language, and detection skills (e.g., drug, explosive, or disease detection dogs). Strict protocols must be established to ensure the animal is responding to the actual stimulus and not to the handler’s cues.

Modern Examples

The phenomenon is not limited to horses and has been observed in various areas:

Canine Training and Detection: Detection dogs can, at times, be influenced by their handler’s expectations. If the handler believes there is a scent in a specific location, they may involuntarily change their pace or posture when approaching that spot, causing the dog to “mark” the source of the handler’s non-verbal cue instead of the source of the scent.

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The term is also sometimes used to describe situations where an AI model appears to be learning a complex task, but is actually learning to exploit a superficial, unintended clue or artifact in the training data to get the answer, rather than the desired underlying skill.

Human Studies: It relates to the Placebo Effect and Expectation Bias in clinical trials, where the beliefs of the doctor or patient about a treatment can influence the perceived outcome.

In summary, the Clever Hans Effect is a powerful reminder of the subtle and often unconscious interconnection between the observer and the observed, compelling science to be rigorous to ensure that results reflect the reality of the studied phenomenon and not human expectations.

The Double-Blind Experiment

The double-blind experiment is considered the “gold standard” (the most reliable reference) in research methodology, especially in clinical trials, due to its effectiveness in neutralizing conscious and unconscious biases, such as the Clever Hans Effect and the Placebo Effect.

Definition and Basic Protocol

A study is double-blind when neither the participant or test subject, nor the researcher or evaluator who interacts with the subject (or takes the measurements) knows which experimental group the subject has been assigned to.

A. Key Protocol Elements

Randomization: Participants are randomly assigned to the different study groups. This ensures that any unknown confounding factors are distributed uniformly among the groups, increasing the likelihood that differences in results are due only to the intervention.

Intervention Groups: Experimental Group: Receives the active treatment (drug, therapy, intervention, etc.) being evaluated. Control Group: Receives an identical-looking inactive treatment, known as a placebo (sugar pill, saline injection, simulated therapy), or receives the current standard treatment.

Blinding: First Blind (Participant): Participants do not know if they are receiving the active treatment or the placebo. This helps control the Placebo Effect (the real or perceived improvement based solely on the belief of receiving treatment). Second Blind (Researcher/Evaluator): The people administering the treatment and/or evaluating the results (doctors, nurses, technicians, etc.) do not know what substance or intervention each participant receives. This neutralizes the Experimenter/Handler Bias (Clever Hans Effect) and Observation Bias (the tendency to interpret or record data to match the expected hypothesis).

Coding and Decoding: An independent third party (often a pharmacist, a statistician, or a data monitoring committee) is responsible for preparing the treatments and keeping the coding key that reveals which code corresponds to the active treatment and which to the placebo. The code is kept sealed until all study data has been collected and recorded and the primary analysis is complete.

Purpose: Neutralizing Bias

The main objective of the double-blind design is to eliminate the subjective influence of both the subject and the observer, ensuring the objectivity and validity of the results.

The double-blind experiment is considered the “gold standard” (the most reliable reference) in research methodology, especially in clinical trials, due to its effectiveness in neutralizing conscious and unconscious biases, such as the Clever Hans Effect and the Placebo Effect.

Scope and Variations

A. Fields of Application

Pharmacological Clinical Trials: This is where it is most commonly used to test the efficacy and safety of new medications, vaccines, and medical devices. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences: It is used to study the effectiveness of therapies, training techniques, or the influence of stimuli, ensuring the experimenter doesn’t “guide” the subject. Research in Sports Science and Nutrition: To evaluate supplements or training regimens, ensuring that neither the athletes nor the coaches know which interventions they are receiving.

B. Common Variations

Single-Blind: Only the participant does not know the treatment they receive (the Placebo Effect is controlled), but the researcher does know (the Experimenter Bias remains). Triple-Blind: A third level of blinding is added: The participant doesn’t know the treatment. The researcher/evaluator who interacts doesn’t know the treatment. The data analyst (the statistician who processes the information) also doesn’t know the coding key that associates group A/B/C with the active treatment/placebo until after the preliminary statistical analysis has been conducted. This prevents any bias in the way data is analyzed or presented.

Limitations and Ethical Considerations

Although ideal, the double-blind method is not always possible or ethical:

Identifiable Interventions: It cannot be applied if the intervention has obvious effects. For example, in studies comparing surgery with a pill treatment, blinding is impossible or very difficult.

Ethics: It is not ethical to withhold a known vital treatment to assign it to a placebo group. In these cases, the control group receives the current standard treatment instead of an inactive placebo.

Logistical Problems: It can be more costly, complex to organize, and require the involvement of more personnel to maintain the blinding.

Unblinding (Breaking the Blind): In some cases, a treatment may produce such distinctive side effects that the blind is “broken” (the participant or doctor deduces which group they belong to), which requires special notation and analysis in the study.

Leave a Reply