The Existential Void Behind Urban Crime

Urban crime isn’t always born out of hunger, revenge, or greed. In 21st-century major cities, its roots are often more invisible: loneliness, lack of purpose, the breakdown of community, and disillusionment with society.

This phenomenon, described by sociology as anomie, has evolved over time into a form of modern existential void: a disconnect between the values society imposes and the real possibility of achieving them.

In this article, we explore how contemporary anomie fuels urban crime, what theories help us understand it, and how this social mismatch is reflected in the streets, neighborhoods, and the lives of those who feel they have nothing left to lose.

🧩 What is Anomie?

The concept of anomie comes from the Greek a-nomos, meaning “without law” or “without norm.”

It was developed by Émile Durkheim in the late 19th century to describe a state of social disorganization where norms lose their regulating power. In a context of accelerating changes—economic, cultural, or technological—people no longer know what is right, what is wrong, or where they should be headed.

Durkheim observed that anomie appeared especially in modern societies where competition, individualism, and inequality generated frustration and a loss of meaning. In his work Suicide (1897), the French sociologist explained that anomie could lead not only to delinquency but also to despair, apathy, or suicide.

Decades later, Robert K. Merton reinterpreted anomie from an American perspective. According to him, modern society promotes goals of success—wealth, status, power—but fails to guarantee the legitimate means to achieve them. The result is a mismatch between ends and means that pushes some people toward deviant innovation, i.e., crime as an alternative way to obtain what society demands they possess.

🌆 Anomie in the 21st Century: The City as a Stage for the Void

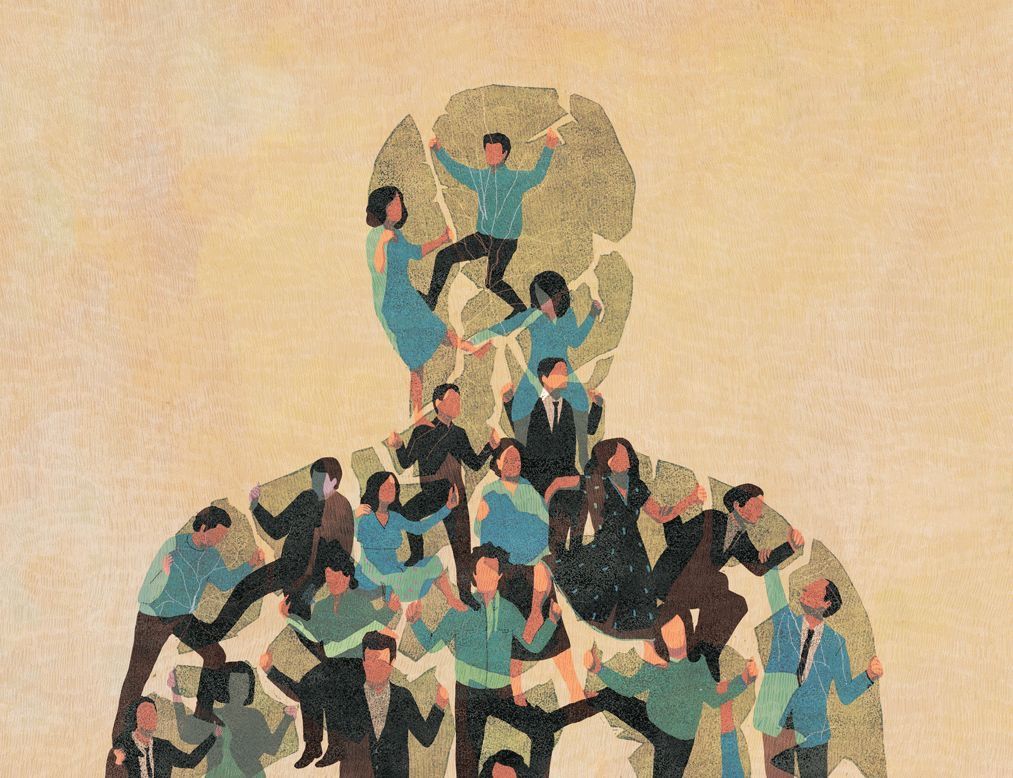

Today, metropolises are the epicenter of modern anomie. Crowded, hyper-connected, and unequal cities produce a new kind of disorientation: that of the individual surrounded by thousands of people, yet profoundly alone.

In this context, urban crime is not always a direct consequence of poverty, but of a crisis of meaning. The anomic subject doesn’t steal just to eat, but to feel part of something, to assert themselves in a society that ignores them, or to escape existential boredom.

Some characteristic factors of this modern anomie are:

- The loss of community: Formerly cohesive neighborhoods become fragmented. Neighborly relations disappear, and distrust replaces solidarity. The individual becomes anonymous in their own environment.

- The culture of instant success: The pressure to show achievements—money, appearance, social media popularity—generates frustration when those standards are not met. Crime can become an “efficient” way to gain recognition.

- Institutional disillusionment: Political corruption, impunity, and inequality reinforce the idea that rules only serve the weak. If no one follows the rules, why should I?

- Technological alienation: Paradoxically, digital hyper-connection has intensified loneliness. Networks display perfect lives that accentuate the feeling of personal failure.

- A precarious economy: Job instability, unaffordable housing, and low wages contribute to a feeling of uselessness and hopelessness.

🧠 The Psychology of the Void: When Crime is an Emotional Response

The modern urban offender, often young, acts not only out of material necessity but to fill an existential void. Their behavior can be understood through different psychological theories:

- Social Learning Theory (Bandura): Criminal behaviors are learned by observing successful models—in the neighborhood, in pop culture, or even on social media. If society glorifies power, easy money, and rebellion, crime becomes a narrative of success.

- Hopelessness Theory (Beck and Abramson): The perception of having no control over the future generates apathy and impulsive, even self-destructive behaviors. Crime becomes a way to “exist,” even if violently.

- Moral Disengagement Theory (Bandura): People justify their immoral acts when the environment seems corrupt or unjust to them. “Everyone cheats; I’m just adapting” becomes the motto of the urban anomic.

- Existential Vacuum Theory (Frankl): Humans need a purpose. When life lacks meaning, the desire arises to fill the void with immediate stimuli—pleasure, risk, money, or power.

⚖️ Anomie and Crime: From the Individual to the System

Urban crime can then be seen as the visible symptom of a deeper social ailment: the decomposition of collective ties and the absence of shared horizons.

Durkheim affirmed that society functions thanks to a balance between individual aspirations and collective norms. When that balance is broken, chaos appears: anomie.

Today, this chaos takes subtle forms:

- Youth without opportunities who seek identity in gangs or violent groups.

- Disillusioned citizens who justify corruption as “the only way to get ahead.”

- Isolated individuals who see crime as a form of escape or self-assertion.

- Masses who no longer believe in the law because the system itself does not respect it.

Modern anomie is not just a phenomenon of marginalized neighborhoods; it is also found in offices, universities, and digital environments where ethics are diluted in the search for success.

🏙️ Examples of the Urban Void

- Graffiti and vandalism as an existential cry: Many acts of vandalism do not seek to damage but to leave a mark. In cities where no one sees you, writing your name on the wall is claiming existence.

- Theft as an assertion of power: More than an economic goal, some thefts respond to the desire to invert hierarchies: the one who never has control takes it by force.

- Youth violence as collective identity: Gangs offer what society denies: belonging, respect, purpose. Their moral code replaces the void of the law.

- “Everyday” corruption: In contexts where institutional injustice is the norm, small corrupt acts are seen as defense or settling scores with the system.

📚 Theories That Help Understand Modern Anomie

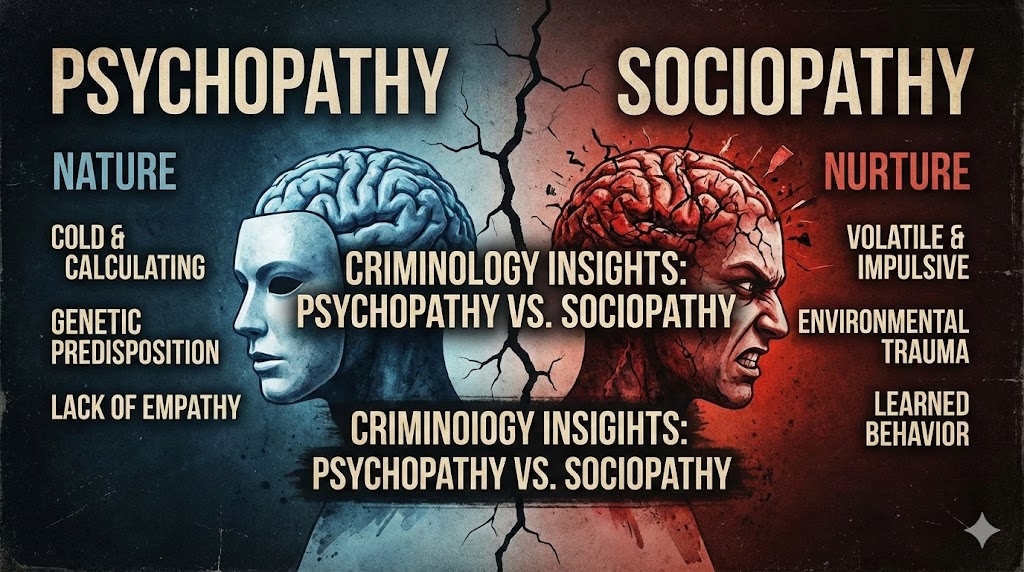

- Strain Theory (Merton): Goals of success (economic success, status) are universal, but the legitimate means are not. → Result: criminal “innovation” as an alternative path.

- Social Control Theory (Hirschi): When social bonds (family, school, community) weaken, the individual disconnects from the norms. → Urban loneliness erodes internal morality.

- Labeling Theory (Becker): Being labeled a “delinquent” reinforces the deviant identity. → Exclusion perpetuates anomie.

- Social Disorganization Theory (Shaw and McKay): Disorganized neighborhoods—lacking strong institutions or cohesion—create contexts where crime becomes part of the daily fabric.

- Alienation Theory (Seeman): The individual feels they have no control over their destiny or connection with others. → Alienation and anomie are two sides of the same void.

💬 Crime as the Language of Disenchantment

From this perspective, crime ceases to be a simple rational act and becomes a symbolic expression: a form of communication in societies that no longer listen. Assault, graffiti, sabotage, or urban violence can be read as desperate messages: “I am here. You don’t see me, but I exist.”

Modern urban crime is understood not only through statistics but through emotions: frustration, anger, shame, a feeling of uselessness. And when the law is no longer perceived as fair, morality disappears. What remains is the void.

🕊️ How is Anomie Fought?

The answer is not just about toughening penalties or increasing surveillance. Anomie is not resolved with punishment, but with social reconstruction.

- Strengthen community ties: Safe public spaces, neighborhood participation, and cultural projects that restore a sense of belonging.

- Restore institutional trust: Transparency, effective justice, and closeness to the citizen.

- Educate in real values, not just productivity: Foster critical thinking, empathy, and purpose beyond consumption.

- Offer life horizons: Policies that generate job, cultural, and educational opportunities to rebuild hope.

- Humanize the city: Design spaces that encourage encounter and reduce isolation.

🧭 Conclusion: The Price of the Void

Modern anomie is the reflection of a society running aimlessly. Urban crime, in this context, is not always born out of malice, but out of disillusionment. It is the desperate response of those living on the margins—not just economic, but emotional—of a system that forgets them.

As long as cities continue to produce loneliness, inequality, and lack of purpose, anomie will remain the invisible fuel of contemporary criminality. Reversing it requires more than laws: it requires rebuilding meaning, community, and hope.

Leave a Reply