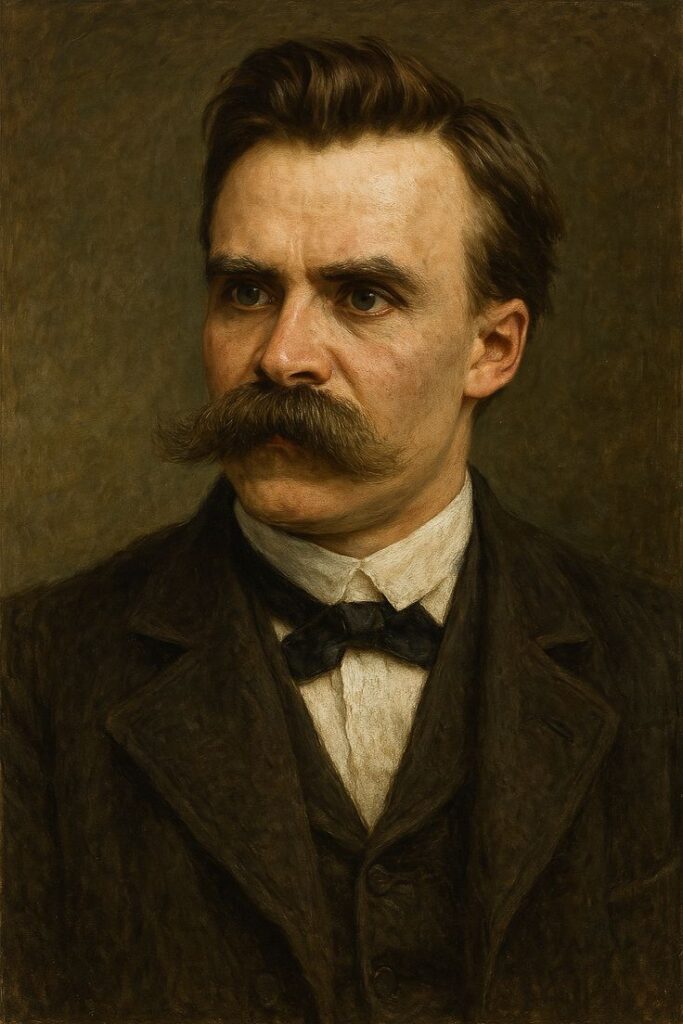

The Übermensch is the ideal of the human being proposed by Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85): someone capable of creating their own values and living in affirmation of life in a world where the old certainties have collapsed (the “death of God”). It is not a “stronger” individual in a biological sense, nor a political leader; it is a normative figure that embodies self-overcoming, ethical creativity, and radical responsibility.

THE PROBLEM IT ANSWERS

- Death of God: absolute (religious/metaphysical) foundations fall.

- Nihilism: a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness.

- Last Man: a conformist, comfortable figure who avoids risk and greatness.

→ The Übermensch is the affirmative response: creating meaning without leaning on transcendence.

TRAITS OF THE ÜBERMENSCH

- Self-creation of values: does not obey “given” values; invents them and tests them in life.

- Affirmation of life (amor fati): accepts even pain and integrates it as fuel for creation.

- Will to power: an energy of expansion, growth, and form (not merely “dominating others”).

- Tragic joy: saying yes to existence with its lights and shadows.

- Solitude and discipline: a critical distance from the “herd.”

- Style: turns life into a work of art (the aesthetics of existence).

THE METAMORPHOSIS OF THE SPIRIT

- Camel: bears inherited duties/burdens (the asceticism of obedience).

- Lion: says “No!” to the dragon of “Thou shalt” (breaks with the authority of the given).

- Child: says “Yes!”, play and the creation of new values.

→ The Übermensch is the creative stage (the Child as symbol).

Transvaluation of all values: to invert/rewrite the values that have turned life against itself (for example, the exaltation of guilt or the denial of the body).

Eternal Return: the supreme ethical test—live as if you would want to repeat this life eternally; if you can say “yes,” you are close to the ideal.

Critique of compassion: distrusts a compassion that infantilizes and perpetuates weakness; prefers to foster strength and growth (note: this is not cruelty, but suspicion of a compassion that negates life).

HOW TO PUT IT INTO DAILY PRACTICE

- Self-governance: decide your principles and uphold them in action.

- Creative projects: produce values/works that add to the world (art, science, enterprise focused on creation, not just utility).

- Character training: cultivate fortitude, intellectual honesty, the capacity to be alone, and personal style.

- Everyday amor fati: integrate errors/failures as material for creation; avoid victimhood.

- Return test: choose and assess actions as if you would live them again infinitely many times.

COMMON MISUNDERSTANDINGS

- It is not racism or eugenics: the Nazi appropriation was a later abuse; Nietzsche criticized nationalism and anti-Semitism.

- It is not social Darwinism: “strength” does not mean trampling the weak, but the power to create oneself.

- It is not a pop superhero nor a political program: it is an ethical-aesthetic and existential ideal.

THE MYTH OF THE CRIMINAL-GENIUS

Confusing the Übermensch with a “superior criminal” is a mistake. The Nietzschean ideal demands more responsibility, not less. Predatory transgression typically springs from resentment or instrumental calculation, not from vital affirmation.

THE MYTH OF THE CRIMINAL-GENIUS

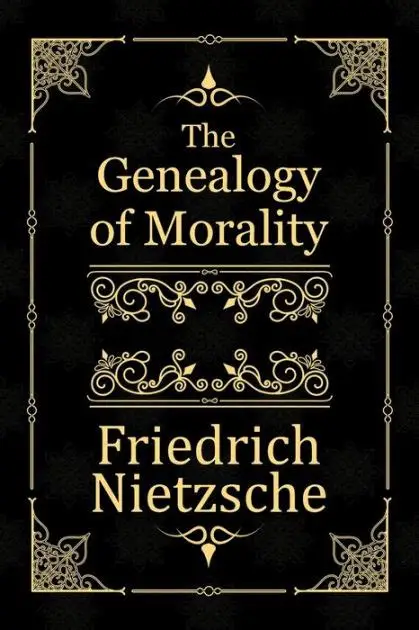

In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche traces the origins of guilt, debt, and punishment as historical constructions, not metaphysical necessities. For criminology: punishment is a contingent social technique. The guiding question shifts from “What retribution is ‘deserved’?” to “Which arrangements increase the power of common life and reduce social resentment?”

COMPASSION, PUNITIVISM, AND STRENGTHENING

Nietzsche distrusts compassion that infantilizes. Applied to criminal policy, this challenges both vindictive punitivism and aid-based approaches that deny agency. The affirmative criterion favors practices that strengthen capacities (of victims, offenders, and the community), avoiding fixed identities of “culprit” or “victim” as essences.

THE ETERNAL RETURN AS AN ETHICAL TEST FOR POLICY

The Eternal Return works as a test: would we want to repeat our penal designs indefinitely because of their real effects? If the answer is no, we need to create others. This approach invites us to evaluate results by cumulative consequences, not only by abstract legitimacies.

OBJECTIONS AND DEBATES

- Elitism? The ideal is demanding (not for everyone), but it does not found “castes”; it is an exigency toward oneself, not inherited privilege.

- Dangerous relativism? Nietzsche replaces transcendent absolutes with styles and hierarchies forged in practice, tested by their vital effects.

- Risk of narcissism? Creative discipline and the “return test” are antidotes to egocentric fantasy.

CONCLUSION

The Übermensch offers criminology a criterion of evaluation that shifts the focus from mere retribution to the strengthening of common life. It helps distinguish deviations that create world from transgressions that impoverish it, and to reorient the discussion of punishment: not as expiation, but as institutional design accountable for its consequences. In short, rather than justifying transgression, the Nietzschean ideal demands creative responsibility: that individuals and institutions live up to the values they claim to profess.

Leave a Reply